Concrete Design Competition & Master Class on ROBUSTNESS

The inaugural cycle of the Concrete Design Competition had as theme ROBUSTNESS. Curator Michael Speaks broadened the notion on ROBUSTNESS to one including flexibility and adaptability, next to sturdiness and resilience. He also added ideas on robust design practices as a means to achieve robust results. A notion that seamlessly extends the ambitions and format of the competition itself.

2003 - 2004

concept, coordination, tutoring, publication

camera

Okke van den Broek

video

bureaubakker

assignment

In this inaugural competition students are asked to submit architectural proposals that engender ROBUSTNESS in/with/through concrete. In order to encourage the most diverse and original designs possible, no predetermined design criteria will be given or stipulated. Submissions are not limited to any scale and can range from small architectural detail, to interior, to free-standing building to landscape proposals. It is expected, however, that all proposals rigorously examine and make use of the manifest and latent qualities of concrete often hidden from view by conventional thinking and normal application. Competition entries will not be judged by stylistic, programmatic, typological, formal or other architecture design criteria, but rather according to the innovative use of concrete to achieve a high degree of design excellence.

ROBUSTNESS: ro·bust adjective [Latin, robustus, oaken, hard, strong; French, robor, robur, oak, strength; perhaps akin to the Latin, ruber, red]. 1a: Having or exhibiting strength or vigorous health: powerful, muscular, vigorous; b: firm and assured in purpose, opinion, outlook; c: exceptionally sound, flourishing; d: strongly formed or constructed, sturdy; 2: Rough, rude; 3: requiring strength or vigor; 4: Full-bodied, strong, as in coffee or wine quotation from Webster's Third International Dictionary of the English Language As indicated in the definition above, there are qualities associated with ROBUSTNESS, such as strength and solidity, which are also the qualities of concrete. Used to lay foundations, to build sturdy bridges and muscular, architectural monuments, concrete, even in its most conventional use, is an undeniably robust material. There are other qualities associated with ROBUSTNESS, however, not conventionally associated with the sturdiness of concrete. Due to the growing importance of complex, adaptive behaviour in all areas of scientific enquiry, ROBUSTNESS has also come to define the degree to which living things, whether single cell organisms, flocks of migratory birds, or complex social systems like ant colonies or metropolises like Tokyo or Mexico City, adapt to changing environmental conditions and evolve over time. ROBUSTNESS, in these contexts, defines a new kind of strength and solidity based on flexibility rather than inflexibility, on suppleness rather than stiffness, on resilience rather than rigidity, and it is this new strength that the competition seeks to explore in/with/through the use of concrete. Specifically, the competition seeks proposals that explore and exploit concrete's more conventionally robust qualities to create unconventionally robust designs whose flexibility, suppleness and resilience make them more adaptable, and therefore more durable, sustainable, hardy and long lasting.

In this inaugural competition students are asked to submit architectural proposals that engender ROBUSTNESS in/with/through concrete. In order to encourage the most diverse and original designs possible, no predetermined design criteria will be given or stipulated. Submissions are not limited to any scale and can range from small architectural detail, to interior, to free-standing building to landscape proposals. It is expected, however, that all proposals rigorously examine and make use of the manifest and latent qualities of concrete often hidden from view by conventional thinking and normal application. Competition entries will not be judged by stylistic, programmatic, typological, formal or other architecture design criteria, but rather according to the innovative use of concrete to achieve a high degree of design excellence.

Michael Speaks, curator

international jury comments - curators summary

Both national and international juries agreed that the competition brief was ambitious and offered a unique opportunity for an industry-sponsored educational initiative. Robustness, the juries also concluded, seemed to provide a strong conceptual framework for developing innovative uses of concrete through material research and product application.

The international jury, which consisted of members from each of the concrete consortium member countries – Turkey, Germany, Portugal, Belgium, The Netherlands, Ireland, United Kingdom, and Sweden – met in April 2004 to judge three entries from each of these eight countries. After three rounds of intense conversation and debate, the jury selected two winners and two honourable mentions from the twenty-four entries. While all jury members ultimately agreed on the winners, there were a number of other entries that the jury thought deserved mention in the commentary. Before moving on to the summary jury comments on the winners and honourable and special mentions, it is worth noting some of the general comments about all the entries.

Among the weaker entries were those that appeared to be adaptations of previous studio projects to the competition brief. This is not a good approach to a competition. In rare cases this occurred by simply adding the word ‘robustness’ to the boards. Even in cases where the work seemed of sufficiently high quality – owing no doubt to work previously completed – these entries rarely addressed the issue of ‘robustness’ in any meaningful way. It was also observed by several jury members that the larger-scale projects – especially those that attempted to address urban issues – were less successful than those that addressed smaller-scale issues. This was not simply a matter of scale; it was not the case, for example, that entries focusing on a single architectural detail or object were more successful. Often, in fact, they were not. Instead, the problem was one of not dealing with the brief. Had they done so, these urban-scale entries might have been encouraged to deal with the city as a robust system rather than treating it as a frame or context for design problems. By contrast, the most successful entries were those where new building systems, components or technologies were introduced. Such systems could be deployed at any scale and were thus considered robust in-and-of-themselves. These entries were easier to discuss on their own merits relative to innovative uses of concrete to develop structural systems that were observably robust. The fact that several prominent structural engineers were members of the jury made such discussions – which included analysis and evaluation of the feasibility of the systems designed – among the more interesting that occurred during the day of judging. There were several entries in this category, however, that failed to make meaningful application of what otherwise was considered rigorous research and testing of concrete structural or component systems. In addition, there were a few entries that had clever or strong concepts that were not sufficiently developed or deployed. In such cases the entry seemed to simply stop after an initial – and in some cases quite successful – proposal. It is also worth observing that the jury was impressed by the relative strength of the entries from non-architectural, or rather non-specifically architectural design schools. This was especially evident in the quality of the presentation materials and the strong conceptual response each made to the brief. But it was also evident in the rigor of material research and documentation of the research and design process.

WINNERS

Rather than choosing one overall winner, the jury decided to award two overall winners, each with 2500 euro prize money. The jury moved through three rounds of discussions. The first round was a general discussion of all the entries resulting in seven moving to the second round. The second-round discussions focused on these entries and decided on four for the final discussion. In the third and final round two entries were selected as overall winners, not so much a compromise but in an effort to recognize two different approaches to the brief.

WINNER ONE

CC001 OPEN SOURCE

UK

The judges agreed unanimously that this was one of the two best entries of the competition. Unlike many entries, CC001 took very seriously the competition brief, elaborating and expanding it not only in their text but also throughout their presentation panels. The project title, Open Source, is borrowed from software developers who share code in an effort to make more robust operating and other forms of computer software. Code becomes more robust when the community participates by working out individual bugs or code design flaws openly and collectively. Accordingly, CC001 deals explicitly with the idea of community and also with how communities evolve and change over time, two issues at the heart of the definition of robustness offered in the brief. Most of the jury felt that this entry dealt better than any other with the brief. CC001 also develops a very strong material research and design proposal. Taking ‘change-over-time’ as its watchword, CC001 showed how concrete could be used to create environments that change according to different needs. A system of concrete tiles that change colour to signal different uses during the week, month and year, is deployed to create environments for the different ways communities use public space. The square, which is constructed from these tiles, is shown in the boards as it might appear over the week and even as it might appear 10 years hence. Though not asked for in the brief, CC001 was also the only entry to prototype an actual design component. Attached to the board is a concrete tile fitted with an electrical plug that changes colour when current is passed through it. This little presentation innovation made explicit CC001’s recognition of the importance of material testing and prototyping. Ultimately, all jurors were agreed that in almost every respect, CC001 is an extremely strong proposal that deserves to be recognized as one of the two winners.

WINNER TWO

TC120 Development of non-directional spatial skeleton structure

UK

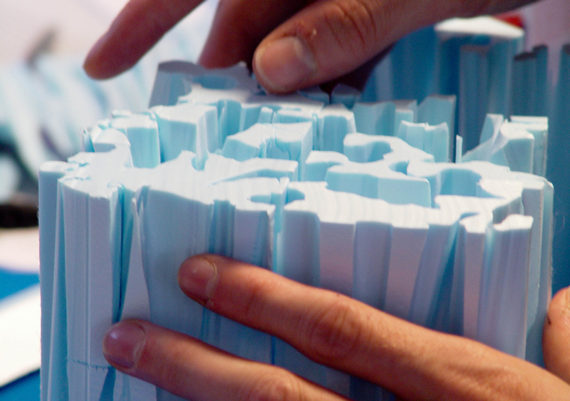

‘A great concept: to live in a concrete sponge! A brilliant idea!’ This is how one of the structural engineers sitting on the jury described the TC120 entry. All of the jury, in fact, agreed that the submission created a uniquely flexible means of building with concrete, and as such dealt with robustness by showing an example of a robust design process and construction system. The proposal is for a construction system that uses pneumatic devices to create what the designers call a ‘non-directional spatial skeleton structure.’ The structure, created from concrete, is one of two control mechanisms that allows the designer to shape a structure using two seemingly incompatible materials: concrete, which is heavy; and air, which is light. Air is pumped into pods which are held in place by the concrete skeleton to form different-sized spaces; air pressure coupled with the skeleton are the design mechanisms that allow TC120 to create cellular spatial pockets more reminiscent of reef structures or soap bubbles than the spaces one normally finds in buildings of similar size. Indeed, the way organic and inorganic systems develop over time is more than a metaphor in this entry. Their process and the final design are, like many natural systems, remarkably adaptive and yes, robust. What is especially impressive in this regard is the iterative and interactive process of designing and testing that took the designers through several phases, adding, with each test, intelligence to their process while at the same time embedding the structural system with its own form of adaptive intelligence. While the jury agreed that the construction system created by this team was very impressive, they also agreed that the application of the system was less impressive. At times, the jury was not sure if the panels for the structural system were part of the same entry as the design, which was conventional and somewhat uninspiring. Nevertheless, TC120 was judged one of the two best entries in the competition.

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

Two entries were singled out for Honourable Mention. Each will receive 500 euro. While clearly among the best entries discussed over the course of three rounds, the Honourable Mentions were not consensus winners; that is, while some jurors felt strongly about them, all jurors did not think they were overall winners and so they did not move to the final round of discussions.

HONOURABLE MENTION ONE

SO124 Hangover

Netherlands

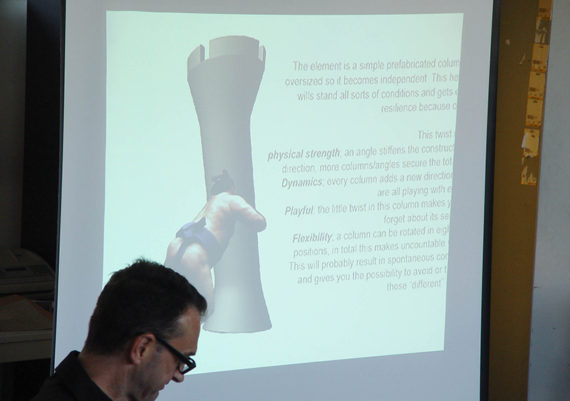

The jury was very impressed with the directness, simplicity, and flexibility of the structural system developed by SO124. The presentation panels dealt with the brief in a rather implicit way by showing a concrete column system performing under many different conditions. A robust system was generated and tested by deploying a single concrete column element in multiple locations, each with its own performance criteria. The panels also made visual reference to natural structures and games that allowed the jurors to imagine the kind of strength and adaptability one might expect from the deployment of the system of columns. Several jurors observed that SO124 made for a new, more flexible domino system – high praise indeed. But the jury also thought that while the system was very robust – even as one juror noted under seismically unstable conditions – it was also limited to the consideration of one element. No mention was made, for example, about how the columnar system worked with floor plates. This relationship, if worked out more fully, might have led to an even more robust system.

HONOURABLE MENTION TWO

DK021 Hazelwood, County Sligo

Ireland

The jury was especially taken with the attention to context, nature, and craftsmanship in the DK021 entry. For some of the jury this entry was one of a very few that focused on the inherent properties of concrete. One juror remarked during the discussion, ‘Now that’s a real concrete project’. DK021 also dealt with the brief implicitly rather than explicitly by developing a dock that interacted with both shoreline and water. The panels featured visual connections with nature and implicitly with natural, evolving systems. The concrete intervention is thus meant as an augmentation rather than a replacement of the relationship between natural systems or boundaries such as shore and water. But while some members thought this a poetic interpretation of robustness, others felt that the entry was rather conventional and showed no truly innovative uses of concrete. Even so, most of the jury members felt it important to recognize such a project with the award of Honourable Mention.

MENTIONS WITHOUT AWARD

The jury felt strongly that the projects selected to proceed to the second round of discussions be recognized at the awards ceremony. These included the following:

NG319

Germany

A much-discussed project. The jury agreed that the project was extremely sensitive, well thought out and executed, but that it was perhaps stretched too thin and trying to cover too much territory. Translation: a bit ambitious for what got worked out in the end.

EB105 An Active Force Within

Germany

Described by the jury as very literary and poetic; but it made no real connection to fabrication or construction. One juror remarked that the entry was conventionally extraordinary. Other jurors said it was a digital storm; others still a digital salad bowl. I would take both as complements.

UW010 Surface Robustness from Surface Condition

UK

Another much-discussed project. Paul Robbrecht, from Belgium, and I, argued strongly (to no avail) for this project which was very focused on material research and fabrication. It was also very beautiful.

I would also like to recognize LS205, Sunken Concrete Decorations, from the Netherlands (one of my own personal favourites), an entry that was much discussed but did not make it to the final rounds. I personally appreciate the innovative nature of this project, but also recognize its real-world applications, especially for fabrication, shipping, and use.

Michael Speaks, curator / jury chairman

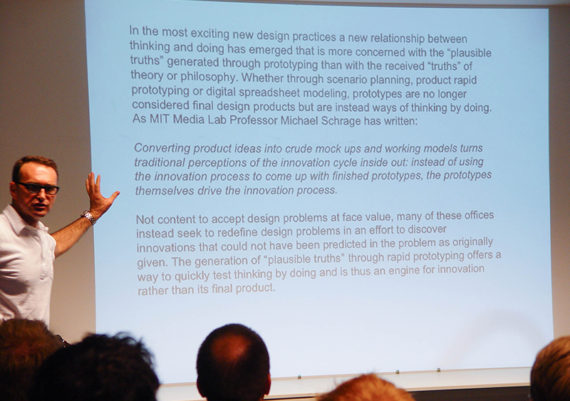

Concrete design master class on robustness

Driven largely by technological innovation, the last decade of the 20th century saw the emergence of what many now call the 'knowledge society'. Knowledge and the raw material from which it is constructed - information - became the most precious resource of governments, companies and individuals alike as they struggled to remain competitive in a rapidly globalizing world. One of the most relevant changes for design in this period occurred with a new relationship between thinking and doing that emerged with new forms of prototyping. Whether through scenario planning, product rapid prototyping or digital spreadsheet modelling, prototypes were no longer considered final products but means of thinking by doing. As MIT Media Lab Professor Michael Schrage wrote at the time: Converting product ideas into crude mock ups and working models turns traditional perceptions of the innovation cycle inside out: instead of using the innovation process to come up with finished prototypes, the prototypes themselves drive the innovation process. In this way, thinking and doing, research and fabrication, and design and designed object become blurred, interactive and non-linear. Design becomes a living, continuous process of creating and testing and as a result more ROBUST.

[Michael Speaks]

The Concrete Master Class on Robustness has targeted a set of objectives ranging from theory on design practice to research into material and general notions of ROBUSTNESS.

Dissolving the distinctions between theory and practice

There is no direct and linear relation between theory or concepts and design, in the sense that theory precedes practice or vice versa. The design process incorporates theory. Any distinction between thinking and making disappears. Thinking becomes making; making is thinking.

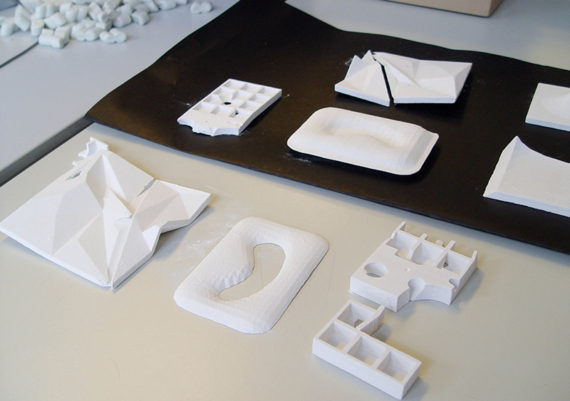

Rapid Prototyping

The unconventional design method of rapid prototyping allows designers to generate and analyze many different possibilities. Instead of focusing research on a few specific results, designers can deploy rapid prototyping to consider seemingly impossible or outrageous variations. A wide area of investigation can thus be covered quickly, opening up the design process to truly unexpected possibilities.

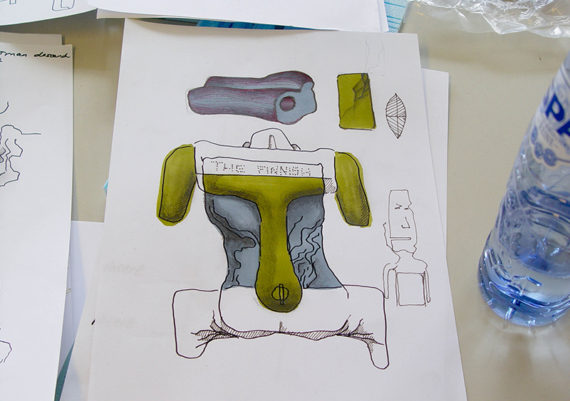

Material research

The master class was driven by material research into different types of concrete. The aim was to uncover the potential of the materials under very different circumstances. Both new and existing materials were introduced in order to investigate the implications of their use for all aspects of architectural design, such as form, program, functionality, and so on.

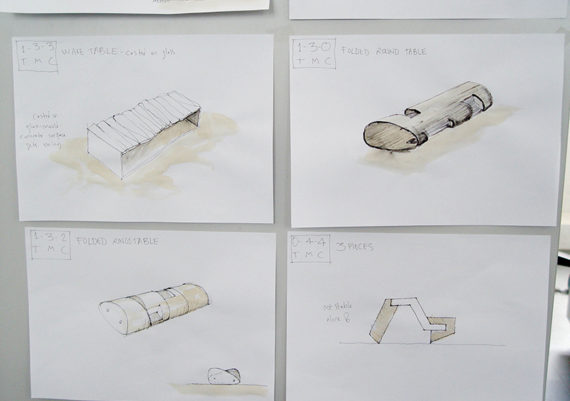

ROBUSTNESS

The assignment for the master class asked for the redevelopment of existing architectural details. These so-called 'primitives' had to be reconsidered and tested using different types of concrete under a variety of conditions. A wide range of possibilities for using concrete therefore had to be explored. The structure of the master class, the research and design techniques involved (rapid prototyping combined with material research), introduced the participants to a robust design approach. The class was open to innovation and to the personal fascinations that included the participants' work on their own competition entries. The master class thus encompassed a whole host of perspectives on ROBUSTNESS generated by the participants themselves.

Working in groups of 5 to 6 people, participants investigated the given 'primitives' through a matrix made up of three axes. One specific area of investigation was represented on each axis.

Axis 1: MATERIAL held four different types of concrete ranging from a standard mortar through fibre-reinforced self-compacting cement to 'imaginary concrete' in which seemingly impossible but essential properties could be projected.

[Generic Standard Concrete / Sophisticated Concrete / Aerated Concrete / Imaginary Concrete]

Axis 2: TACTILITY indicated five different types of surface treatment for concrete. This axis dealt with the formal exterior of architecture. Concerns with formwork, poured and prefabricated concrete were important issues on this axis that ranged from 'straight out of the mould' to treatments that open up the inner structure of mortars.

[Smooth Surfaces / Exposure of Aggregates - intact visual aggregates / Exposure of Aggregates - treated visual aggregates / Structured Surfaces / Special Surfaces - special aggregates]

Finally Axis 3: CONTEXT offered associative inputs for each prototype. Five paintings from Gerhard Richter represented his 'prototyping' practice in which he continuously investigates materials and techniques and, just as importantly, their relations to the actual paintings in terms of representation, formal language and so on. Without any specific directions but the paintings themselves, the participants could either interpret them literally in terms of object or subject or let them act as catalysts for their own associations and fascinations.

[Apple Trees, 1987, oil on canvas, 72 x 102 cm / Reading, 1994, oil on linen, 72,4 x 102,2 cm / Woman Descending the Staircase, 1965, oil on canvas, 200,7 x 129,5 cm / Abstract Painting, 1997, 36 x 51 cm / Abstract Painting, 1997, 55 x 48 cm]

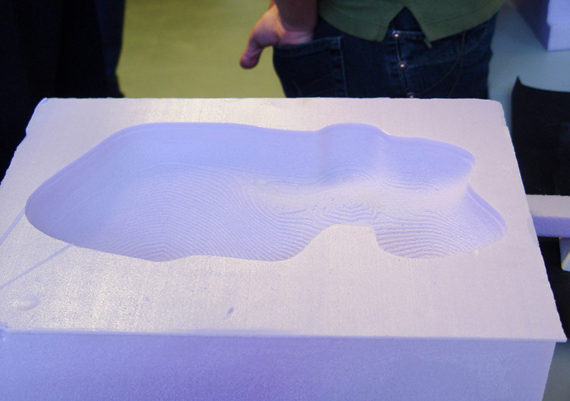

After exploring each primitive through most of the 125 positions on the matrix, each group chose to develop one prototype for production at scale 1:1. During the 'matrix' investigation a number of experts assisted participants on subjects like concrete techniques, CNC software applications, and general design skills. Scale models were produced with the help of Delft University of Technology. Made using CNC-milling and 3D-printing techniques, these models represented scaled versions of prototypes, and details of these prototypes. Perhaps even more importantly, they enhanced understanding of the implications of the techniques on possible end products. Surface conditions and restrictions on possible forms were among the issues studied and tested. The proposals for the final prototypes were presented at the end of the master class in the form of models - some of them in concrete - sketches and 3D renderings. A team of software experts translated the proposals into sets of working files for TwinPlast, a Belgian CNC milling company, which produced the moulds.

The moulds were then sent to different locations for the production of the actual concrete objects. This was the final test in an exhaustive period of research into what Robustness can mean for the practice of architecture.

Kristof de Bonte, Tom Broes, Sebastian kreusch, Thomas van der Velde, Kenny verbeeck, Sönke Gebken, Nils Nolting, Daniel Zajsek, Marjeta Zupancic, Simon Cafferty, David Kelly, Matthew McCullagh, Bas van der Pol, Luc Schouten, Niels Verkooijen, Luis Pedro Ferraz Marques, Tiago Furtado Cabeleira, José Manuel Vacas, Markus Krunegard, Jens Laursen, Jon Mjönes, Sebastian Nagy, Emre Cetinel, Güney Cingi, Levent Firat, Tuba Karpuzoglu, N. Onur Sönmez, Onur Sariyildiz, Basak Ucar, Fransesca Crosby, Christopher Glaister, John Hutchinson, Il Hoon Roh, Thomas Kilvert, Afshin Mehin & Tomas Rosén

curator

Michael Speaks

tutors

Siebe Bakker & Karl Daubmann

critics & experts

Jef Apers, Klaus Bollinger, Guy Chatel, Fred Gladdines, Hans Köhne, Rob Nijsse & Wim Sambaer

lecturers

Bernard Cache & Alejandro Zaera Polo

support

Joost Bonnema, Okke van den Broek, Matthew Louis Miller, Daniel Roos, Daan Roosegaarde, Martijn Stellingwerff & Maarten Veerman

host

Berlage Institute, Rotterdam - Rob Doctor & Francoise Vos

initiative

ATIC - Maria Dulce Louçao

BDZ - Jörg Fehlhaber

BetongForum - Öyvind Elseth & Anita Stenler

The Concrete Centre - Allan Haines

ENCI - Hans Köhne

FEBELCEM - Jef Apers

Irish Cement - Brendan Lynch

TCMA - Çaglan Becan

photography

Okke van den Broek & Maarten Veerman

2004 / English

Documentation on Concrete Design Competition on ROBUSTNESS and master class for laureates, led by curator Michael Speaks. Includes all nominated entries, jury reports and photo documentary on master class. Tetxs by Michael Speaks, Siebe Bakker and Hans Köhne. Interviews with Karl Daubmann, Bernard Cache, Wim van den Bergh, Alejandro Zaera-Polo, Hanif Kara, Annette Gigon & Mike Guyer by Olv Klijn

editor

Siebe Bakker - bureaubakker

graphic design: Manifesta

backflap

'... there are qualities associated with ROBUSTNESS, such as strength and solidity, which are also qualities of concrete. Used to lay foundations, to build sturdy bridges and muscular, architectural monuments, concrete, even in its most conventional use, is an undeniably robust material. There are other qualities associated with ROBUSTNESS, however, not conventionally associated with the sturdiness of concrete. Due to the growing importance of complex, adaptive behavior in all areas of scientific equity, ROBUSTNESS has also come to define the degree to which living things, whether single cell organisms, flocks of migratory birds, or complex social systems like ant colonies or metropolises like Tokyo or Mexico City, adapt to changing environmental conditions and evolve over time. ROBUSTNESS, in these contexts, defines a new kind of strength and solidity based on flexibility rather than inflexibility, on suppleness rather than stiffness, on resilience rather than rigidity...'

Michael Speaks, curator