Blitz Beton Workshop 2001 - Fondant Architecture

The scheme of the Blitz Beton Workshop 2001 was simple: design the missing plinth for the building of TENT.. An assignment that, similar to previous Blitz Beton assignements originates from the conviction that architecture has a strong ‘knowing through making’ component. By making with ones own hands the possibilities of the element becomes clear. With a length of 90 meters, a height of 1,75 meters, exposed to the scrutinizing glances of passer-bys from two streets and within the time limit of 6 days, we had the opportunity to test our proposition.

2001

concept, coordination, publication, tutoring

Fondant Architecture

Documenting the Blitz Beton Workshop Fondant Architecture. Rotterdam, August 2001

film and editing

Erik Jutten & Core van der Hoeven

English / Dutch

The Ultimate Concrete Experience

Making concrete understood as an architectural material of great potential is the aim of the Blitz Beton Workshop series. The word 'blitz' can be associated with 'intense, energizing, and temporary'. Exactly the main elements of the Blitz Beton formula. A full week of learning by doing. Of high speed and high pressure, deriving inspiration in a joyful context. Working in an international atmosphere, with professional facilities and expertise. A temporary concrete result and an everlasting impression on concrete. It is also a unique learning experience: learn to think with your hands and to feel with your mind. For understanding materials is not a matter of books: materials have to be touched, smelled and tasted. Keen interest in materials cannot arise from theories.

Why is ENCI, the Netherlands Cement Industry, in the lead in developing the Blitz Beton program for learning-experiences in concrete? ENCI is a market leader in the Dutch market for cement and concrete and we feel a responsibility to contribute to the education of new generations of architects and structural engineers. We want to be a partner and facilitator for educational institutes, in collaboration with other companies.

The Blitz Beton network of supporting companies extended from the start in 1998 up till now. Now we can count xx companies that have supported the workshops with materials and expertise in a wide range, from concrete mortar to structural consultancy. Please look at the list of companies that supported this year's workshop, on the colophon.

This facilitating role opens new educational possibilities. But we do not want to manipulate the education itself; let us be clear about that. That is why we asked an independent organization, bureaubakker, to be responsible for the educational quality of the workshops. Siebe Bakker, director of bureaubakker, developed the program, chose the supervisors and guided the workshop.

Every year we focus on one specific type of concrete. The first Blitz Beton Workshop, in 1998, supervised by Peter Wilson, focused on prefabricated concrete. In the second, supervised by Zvi Hecker, we did a concrete casting on site, with a very new type of concrete, known as self-compacting concrete.

The third year, we chose to work with foamed concrete, very lightweight, which could be modeled with hand-held tools.

This year we concentrated on sprayed concrete or shotcrete. This allowed us to go beyond the restrictions of formwork with rectangular shapes. The design assessment was to make a new plinth for an existing building, an art exhibition center in Rotterdam city. Four Belgian architects – alternating each day - supervised the analyses and designs, evaluating a selection of designs for execution. In sequens: Bart Macken, Niklaas Deboutte, Karel Vandenhende en Klaas Goris. The participants came up with ideas for applications of sprayed concrete that were never tried before. This was also a challenge for the supporting companies to look for new techniques to make the execution possible.

Final result was a real interesting and interactive façade with organic shapes, inviting passengers to discover the building inside and outside, to use the façade.

I admire the participating students who were eager to use this unique opportunity to design and execute a real façade, optimizing the result, to find out and accept the material’s nature, the way it could be treated best. They tasted the concrete literally and figuratively.

I want to compliment all the participants for their dedication and perseverance. Of special interest was the participation of students from abroad. Maybe it is permitted to mention in particular the students from Eastern Europe, coming from Poland and Romania. It was the first time these countries were represented and we were very happy for that. The multicultural atmosphere was also a key factor to the success.

I also want to thank my colleagues from cement industries in the United Kingdom, Norway, Germany and Turkey, which were willing to sponsor the participation of students from their countries. Within the European association of cement industries - Cembureau - we discussed the possibilities to join our forces, in order to create a collective European approach.

I am looking forward to the fifth Blitz Beton Workshop in 2002; hopefully it will be a Euro Blitz and again an ultimate concrete experience.

Hans Köhne

Hidden Harmony is Stronger than the Visible: Belgian Conditions

Idea

The scheme of the Blitz Beton Workshop 2001 was simple: design the missing plinth for the building of TENT.. An assignment that, similar to previous Blitz Beton assignements originates from the conviction that architecture has a strong ‘knowing through making’ component. By making with ones own hands the possibilities of the element becomes clear. With a length of 90 meters, a height of 1,75 meters, exposed to the scrutinizing glances of passer-bys from two streets and within the time limit of 6 days, we had the opportunity to test our proposition.

The topic of the plinth, or more general that of the facade, is within the architectural practice traditionally the domain of composition and proportions. However, it is not a purely esthetic issue because a facade forms both the face and the epidermis of a building. To accommodate this double function there exists roughly two approaches; from outside and from inside. Under the influence of the ‘modern’ the understanding of a neutral facade prevailed. The facade as (white) background. Ordered according to industrial schemes and seen as a separate element draped around the structural skeleton. A development leading to the modern ‘curtain wall’ and its mediocre potencies. Taking the modern skin of several centimeters thickness as decor, we asked ourselves how this position changes as a new facade is added, but now made out of a structural material: sprayed concrete or shotcrete. In other words, what will happen if the curtain becomes a carrier?

Location

Bearer and simultaneously exposé for our temporary skin is TENT. in Rotterdam, a center for modern art. Important characteristic of its exhibitions is their notion of art as a domain that is continuously developing, open to new influences. To communicate this notion, their policy is to simultaneously organize exhibitions with overlapping timing. In this way there is always a productive mixture of building up, exposition and clearing out. This dynamic of TENT. is hidden behind the classical composition of their facade, a former girls school in the Witte de Withstraat. Itself a street with its own dynamics of the ‘regular’ Rotterdam street life.

The location offers two worlds that rarely meet. Our experiment was to find out what would happen if these different worlds would be confronted with each other. If in other words if something would be done about the borderline in between both: the facade. An assignment that also is interesting from an architectural point of view because the composition of TENT.’s facade is classical but incomplete. Its rustic plinth is missing!

Supervisors

To afterwards design a plinth for an exhibition space that (temporary) binds the street and exhibition is a complex exercise. An assignment that asks for much and for a lot of different input from experts. The didactic exercise in this workshop was therefore seen as a relay race. Four different architects were asked to join the project for 24 hours each. The rely team existed, in order of appearance, out of Bart Macken, Niklaas Deboutte, Karel Vendenhende and Klaas Goris. Besides their tutorship for one day each of them held a public lecture on the eve of their supervision.

The choice for sheer Flemish architects is no coincidence. For several years an architectural practice develops in Flanders that appears extremely effective in a fragmented and layered context of urban situations. In this approach contextuality, pragmatism and commonplaceness are combined in various ways. It is striking that the products are down to earth and realistic without becoming simplistic or boring. After a long lasting disdain for the chaotic urban landscape of Flanders the situation has changed. A manner is developed for working with fragmentation. An approach that appeared in all lectures by emphasizing notions as straightforwardness, separation of public and private in relation to the absence of ‘tabula rasa’, the practice of the extension, the washhouse, the scullery and the storage space and the surprising perspective when old and new are intertwined.

Result

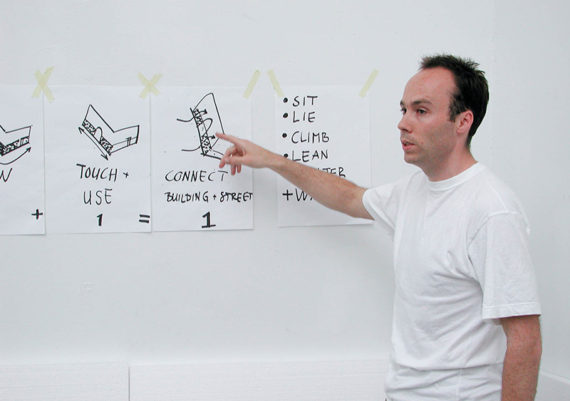

The result of this bombardment of information was of course chaos. After three days of discussions and presentations, the goal: to collectively design one plinth, seemed further away than ever. Every attempt to come to agreement between the different ideas failed. The only solution seemed to introduce a less subtle and less contextual but in every regard a Flemish approach; zoning. The whole surface of the plinth was rigorously divided in more or less equal plots. Using this zoning plan a troika of ‘master planners’ was chosen from the students. Within a few hours they had to draft a basic layout for the works. The rest of the students formed like-minded groups. The sizes of these groups were used to assign a number of plots to be used. Afterwards a timetable was pronounced in which the master planners would announce ever more detailed plans and regulations. With two more days to go a process started of negotiations (and bribes), construction, judgments, demolishing and new starts. The assignment immediately changed from an architectural into an urban planning one. Suddenly the previous endless discussions appeared to be fruitful. There was no blockade anymore from a comprehensive architectonical image. In stead there was a will to achieve an urban scheme. Helped by the structural freedom of the material a collection of ideas aroused. Ideas visually far apart but connected by the starting point of zoning. It became a series based on the notion of the façade as utensil, a façade to sit on, to lean at, to stand on and to touch.

Olv Klijn

Four Lectures on the Belgian Condition

Bart Macken

The office of Macken & Macken now exists of six people. Their work, like that of many other Belgian architects, started with housing. Unlike many other Belgian architects they have always regarded the private house as the most important laboratory for architecture. In his lecture Bart Macken therefore showed three examples and their relation(s) to recent projects outside housing.

One of the first houses the office made was that of a farmer in Muizen. Since the house would inevitable occupy a part of the client's means of living – i.e. agricultural land - Macken & Macken designed a house with a minimal footprint. By introducing into this minimal footprint house a split-level organization the client got a maximum freedom. During the day the connection with the land prevails, only de bottom part of the split-level (which houses the kitchen) is used. At nights the hovering upper part of the house offers an opportunity to disconnect to the land and a have a life of ones own.

The next house Macken showed was the suburban house the office is constructing at this moment. The context for this house is what Macken calls typical for the Belgium condition. The house is situated on a very narrow plot – 15 meters wide – so one can at most be 3 meters away from the neighbors on both sides. Plots like these are very common but they are rarely used in an inventive way. Therefor the challenge in this case was to design a house that would respond to this situation, use its context. “What we did was simply put a terrace on the south side of the house and in doing so cut out a large piece of the house.” This intervention opened the plot, both from inside the house and from the street. From inside there is an opportunity to look across the plot and from the street you catch a glimpse of what is going on in the yard. A play of ‘opened and closed’ was put in place here.

The third house that was shown is situated near Leuven. The context for this house is a good example of another extreme: a plot at the edge of agricultural land and a village. The plot itself is small but the view is immeasurable. The client asked for a house that could be used under different circumstances. Macken & Macken gave him three houses. Ground level has the living space that is open to all sides with a beautiful view. Since this is a very open space it can also be used as a space for parties and receptions. The basement of the house contains the studio. Here the client – a painter – can step back from the rest of the world and concentrate on his work, only one view to the land is left open. The top part of the house contains the sleeping areas. From the street this part looks completely closed but in fact it has a courtyard to give light to both the bathroom and the master bedroom.

After this row of housing experiment Macken showed the projects the office is working on now. Projects ranging from a theater in Turnhout to several small commissions for the Belgian government across the country. All of these projects however showed the lessons the office has learned while making houses. They all show this attractive mix of comfort and excitement that a good house offers.

Niklaas Deboutte

Niklaas Deboutte presented the collaborative work of META Architectuurbureau; an office founded in 1991 together Eric Schoors and Bart Biermans. ‘’Our philosophy is that all good things don’t take long. In our work we therefor cultivate a certain laziness.” Especially in Belgium where there is total chaos when it comes to building one has to be pragmatic and re-use good solutions. Another difference with for instance the Dutch situation is that although everyone in Belgium agrees that they have created a ‘monster’ in terms of legislation, nothing is done about it. In this situation only creative minds can survive. The result is that in Belgium one often comes across almost surrealistic situations that are in fact part of reality.

The Belgian history of promoting country life and subsidizing suburban spread resulted in what the situation is today: a dispersed city at the scale of a country. The most common architectural commission in this city is housing. This is what every Belgian architect starts with and META was no exception. The first project therefor to be shown was a house. A house on a extraordinary site, on the edge of a residential area, a shopping area, a football field and 100 meters away from the start of the runway of the airport of Oostende. Although it is a very simple house its construction was announced to pilots allover Europe. They all knew that there was a house under construction at Oostende, and they had to watch out for the crane that was involved. (Because of the planes the crane had to be taken down at nights and weekends.) This is just one example of a surrealistic situation that in Belgium is just reality. Other countries simply don’t allow people to build on places like these, but an airplane lover in Belgium can live practically on the runway.

The first project META constructed is less surrealistic but still remarkable. The commission was to build a house for just 3 million Belgian Franc’s. A very tight budget and no other office took the commission, but META thought they should try it. They agreed with the client that he would have noting to say in the design process. The only thing he would submit was his program, his budget and the location for the house. Also the client told META that he would be willing to do all possible simple construction jobs himself. By offering the client a simple archetype house META managed to satisfy the client.

The building for Elektro Loeters in Oostende most clearly expresses the conflicting building rules in Belgium. In order to have this building build META had to play a trick. According to local rules the FAR for this building should not exceed 1,8. Also the building was to have a pitched roof. These two rules made all options simply uneconomical. One would for instance end up having a building with a depth of just 3 meters. Even after showing to the local authorities that the rules where wrong nothing happened. Niklaas Deboutte contacted another architect who was facing the same problem in Oostende, bOb van Reeth. Van Reeth told them to simply take out one floor of the building in all the drawings. After they got the permission to build this floor of course was added again and the building was build as it had originally been designed.

This is what META likes to call laziness. It has nothing to do with not working hard but with applying common sense, slyness and intelligence. It is this attitude that is indispensable if one wants to build in Belgium.

Karel Vandenhende

Karel Vandenhende recently started his own architectural office. So far two projects have been realized. One is the interior of his own apartment in Brussels and the other is the conversion of two residential blocks in Gent. Besides these practical results Vandenhende showed numerous examples of projects that are the result of a changing architectural climate in Belgium – i.e. the introduction of a ‘master architect’ who coordinates government policies. . The new projects that Vandenhende showed are all conceived in collaboration with other young architects for small competitions allover Belgium. They offer a glimpse as to what Belgium might look like in five or ten years from now.

An example of one of this project is Vandenhendes design for the competition ‘Home-work’ in the village of Ettelgem. The assignment was to design twelve houses on a plot along one of the main roads. In his design Vandenhende used the main characteristics of many Belgian villages in general: their blind facade or ‘wachtgevels’. What happens is that houses along main roads are built in an irregular pattern. The only things they have in common is that they stand alone on a plot and their side facades are ‘blind’, to offer the possibility of attaching a new house – which never happens. Vandenhende designed three small blocks that fit into this situation. The blocks have more or less the size of the surrounding houses. Their irregular positions and their blind side facades make them even look completely adapted. The internal organization with three apartments per block however is of course a world of difference with their neighbors.

The second project Vandenhende showed was his conversion of two residential blocks in Gent. The task here was to change an existing two-room apartment block into a block with four-room apartments. By analyzing the original plans Vandenhende discovered that the only thing he would have to do was taking out the original staircase and place a new one outside the building. After having placed the stairs outside Vandenhende had apartments that basically existed out of one big space at the back of the block and a corridor like space with all services at the front. Because of regulations this open space had to be organized in to smaller rooms, Vandenhende therefor added division walls. The trick with these walls however is that they are very simple and hardly more than a temporary division. If one wants the space can easily be reconverted into one open space. In this open configuration only the distance between different functions gives a sense of privacy.

The third project that Vandenhende showed was a direct result of the project in Gent. Since he won the competition for the apartment blocks in Gent Vandenhende needed an office and office space. He went to Brussels and bought an apartment on the 24th floor of a skyscraper. This apartment with windows on three sides offers a spectacular view on the chaos of metropolis. 24 hours a day and 7 days a week one sees movement and change from this position. In order to make this place into a workable apartment that could also function as an office Vandenhende thought he should create an almost neutral environment. By taking out every wall that could be taken out Vandenhende created an open space with four boxes that contained vertical shafts. The boxes stood in an irregular pattern. This configuration gave Vandenhende the idea to organize all other things in his apartment in box-like volumes that could move trough the space and in doing so create different spaces – i.e. an configuration for living and another for working etc. This project is a clear example how Vandenhende focuses on the in-between spaces of both interior and exterior space. In the rest of his lecture this focus was elaborated in several competition designs. Designs that often operate on the edge of inside and outside. Houses for instance that uses the facade of the neighbors as a visual ending or the creation of public indoor and outside routes (connections) in an existing village with the careful positioning of three buildings. In other words Vandenhendes focus on the in-between seem both logical and rewarding since there is a lot of ‘in-between’ in the spread city of Belgium.

Klaas Goris

Klaas Goris can be considered the Nestor of the four architects we invited for Blitzbeton ’01. With his office Coussee & Goris he has realized projects that shaped the architectural generation we saw in the pervious three lectures. Due to circumstances his lecture had to be improvised, yet it revealed still another typical Belgian condition. After a focus on the private house, on laziness and on the in-between space, Goris showed projects dealing with the context of industrial heritage. A context that in Belgium is very common due to its early and widespread industrialization.

The first interest in all the projects of Coussee & Goris has always been to build. Of course one needs concepts in order to develop a design but these concepts vary from one project to another. Yet the concept that runs through all the projects as an underlying strategy is that of creating something that can actually be realized.

The first project Goris showed was that of BACOB Bank in Dendermonde. The assignment was to design a new office for the bank at the site of a formal factory. The situation existed out of a classical building (re-build after demolition in the Second World War) and a factory hall behind it. Instead of taking away the factory Cousse & Goris took out all its dividing walls. What was left was an incredible roofed public parking that only had to be linked to the classical building on the street side. For this purpose a little glass volume was introduced. By carefully making a cut in one of the side facades of the factory hall Cousse & Goris also offer a view on a chapel that is not visible from the street since it is completely surrounded with high buildings.

A project that took the question of how to re-use factory buildings to a new level was that of formal textile factory. Here a big industrial complex was completely redesigned by Coussee & Goris. What they did was again more or less strip the building from all its dividing walls. Than they introduced a system of sliding walls and curtains that could divide the space into variable sizes. By also introducing permanent elements such as bars and escape routes the complex became ‘programmable’. The result is a building that can be used for many things and many things at the same time. All spaces can be rented almost per square meter.

A similar strategy was used to create a new space for the office itself. In Gent Coussee & Goris bought an old factory building for very little money. Because much of the building was still usable they only put on a new roof. Many of the old steel window frames where also taken out and replaced by single plates of glass that where mounted from the inside. When viewed from an angle these new windows turn into big mirrors that almost symbolically represent infinity, infinite use of buildings in this case.

The last outstanding example in dealing with a delicate historical context is the project the office did for the tourist information in Gent. The new office of the tourist information was to be located in one of the oldest buildings in the city. Instead of taking out all that was unnecessary Coussee & Goris just add what was needed as a temporal program. They designed a system that, like the systems on which modern factories are based, can easily be extended or pulled down. All new facilities are grouped in a beam shaped element that is put in the historical interior. This new volume is completely self-supporting and only touches its context on a few spots.

Beside the many examples Goris showed of completely new buildings the ones that are described here where most remarkable. They complete the architectural picture of the ‘Belgium Condition’.

Fondant Concrete Architecture

The objective of the workshop was to design and create a plinth, consisting of a series of architectural objects, by using sprayed concrete, which would form a new, temporary façade of TENT. Centre for Visual Arts in Rotterdam.

The total area available for our experiment was about 90 sqm and it stretched over two sides of the building, the front and the side elevation.

Due to this high visual exposure, any intervention on the existing building is bound to attract interest, not only on the pedestrian and street scale, but also on the city scale.

An important fact to mention is that although there were about 30 participants, most of whom have never met before, we were all there working together on one single project.

The project set off with formation of six groups, each comprising of about five people.

Working in groups with tight deadlines was very challenging, nevertheless productive, and soon we were coming up with working models, diagrams and drawings explaining our proposals. And although the concepts of different groups were very similar, when it came to choosing one design only the problems arose.

Hours long discussions ensued with unavoidable emotional roller-coaster, speeches from potential leaders, and interventions from our Belgian advisers.

With the time ticking away there was every reason to worry, as results of days of our research and design have been jeopardised by the lack of our productivity on communication level.

However, as every step backwards is a step forwards, in our case it was the change of our strategy that put us back on track and kept the project going.

A master planning committee was set up and a series of rules proposed which were to guide us in making of our decisions. The total area was divided into six zones – one for each group, where each group was able to develop its design within the acceptable rules, with their design still forming a part of the whole design.

And although this all sounds very complicated and confusing, the advantages of such a system proved very useful during the final assessment of the project.

As each group was given freedom do design and construct their own zone, we were able to compare the advantages and disadvantages of different construction methods and their influences on the finished design and its qualities. The three-dimensionality of the façade and different forms were achieved through the use of wood, polystyrene and stucanet.

The finished project was a flowing, undulating surface comprising of curvilinear as well as purely geometric forms, expressed through waves and craters, hidden compartments and skeletons, all open up to different readings and uses.

During the spraying process and afterwards it became apparent that some areas worked better than the others in terms of achieved final result. There were also some problem areas, for example with curved, projecting forms where the sprayed concrete succumbed to its weight and came off.

There were many surprises, especially relating to our idea of textures and the final appearance of the surfaces.

A lot of time had been spent on discussing how surfaces could be altered, made smoother or rougher in order to achieve different results.

However, at the end of the day, due to a number of reasons it was not possible to greatly manipulate the already sprayed concrete.

The time span within which the project was undertaken and executed, the location of the building and the nature of the project – temporary installation – were all the determining factors of the technicalities of the project.

As there was only one day available to spray the whole of the façade, and as the façade becomes a public installation it was necessary for the concrete to be able to dry fast. This in return asks for other conditions to be fulfilled, such as the right agent and pressure under which to spray.

TENT. is located on a relatively busy street, rich with street life, cafes, shops, flats and parked cars with little space left for manoeuvring large vehicles such as concrete mixer.

The whole execution of the project evoked a lot of interest from the locals as well as from passing cars, pedestrians, TV stations and the press. It became an installation on its own.

At the end of the day there was an overwhelming sense of joy and achievement among all of us, and a big relief for our organisers.

Talking to most students from the workshop, who are mainly from architectural background, and at different stages of their education, it is generally believed that most architectural schools and their academic curriculum offer little opportunity for us students to engage with and explore the potentials of the materials that we are specifying and designing with.

Some schools have acknowledged this issue and, as it is the case with our college, the Royal College of Art in London, have incorporated shorter projects into the curriculum that would cater for such needs.

However, the value of this workshop is that it allows us to work with materials on a larger scale, whereby the impact of the final design is not only felt within the boundaries of the school but it is also exhibited to a wider audience, the city, making it an object open to a wider criticism. And criticism is something that is part of our profession, and that we as architectural students need to get used to.

At the end of the day, this workshop was not just about experimenting and learning about materials. Its wider relevance lies in learning to work together. At the time when architectural practices are becoming more and more international, and younger people are moving from country to country in order to gain a wider architectural experience, it is becoming increasingly important to learn to communicate and work as a team. This project demonstrates how difficult it sometimes gets when working in a large group, but also it shows that we have managed to move on and keep the project going.

Projects such as this one are immensely important to students of architecture, and they should, ideally, become more integrated into our education.

This project is also a good example of industry getting involved and taking responsibility towards education of the next generation of architects and engineers.

I hope that projects like this will find a welcoming reception and a broad encouragement from educational institutions as much as from the industry

Dinka Izetbeckovic

Excerpt from the original published by Concrete Quarterly issue 200, Autumn 2001 - www.concretequarterly.com

Kristina Bacht, Klaus Birthler, Jesse de Bosch Kemper, Ivo van Cappeleveen, Bart Cosyn, Ola Czech, Martijn Eefting, Gregg epps, Pablo Guerrero, Hedwig Heinsman, Dinka Izetbegovic, Marita Jacobsen, Joep Jansen, Kemal Kavas, Friso Leeflang, Maren Leutgens, Rannveig Nyegaard, Oretsis Pangalos, Ide Reckman, Dennis Rietmeyer. Gerald Russelman, Kathy Stertzig, Klara Veer, Rogier Verkaik & Jeroen van Wieren

supervisors

Niklaas Deboutte, Klaas Goris, Bart Macken & Karel Vandenhende

tutors

Siebe Bakker & Olv Klijn

support

Fred Gladdines, Hans Köhne & Stylos

supporting companies

Aronsohn Consultants, BIM, Cementbouw Heemstede, Masterbuilders & PontMeyer

special thanks to

Tom Croes, Manifesta, The Maze Corporations & De Twee Snoeken

host

TENT. Centrum Beeldende Kunst Rotterdam - Ove Lucas & Arno van Roosmalen

initiative

ENCI - Hans Köhne