transferring architecture to movies to concrete objects

The Camera Eye project, for master students of the Delft University of Technology - Architecture, researched film as a representational medium in architectural design practice. Our workshop took the storyboard and camera track proposals back into the realm of architecture. Transferring them into material objects.

2004

concept, coordination, tutoring

camera eye research studio

‘I’m an eye. A mechanical eye. I, the machine, show you a world the way only I can see it. I free myself for today and forever from human immobility. I’m in constant movement. I approach and pull away from objects. I creep under them. I move alongside a running horse’s mouth. I fall and rise with the falling and rising bodies. This is I, the machine, maneuvering the chaotic movements, recording one movement after another in the most complex combinations.

Freed from the boundaries of time and space, I co-ordinate any and all points of the universe, wherever I want them to be. My way leads towards the creation of a fresh perception of the world. Thus I explain is a new way the world unknown to you.’

(Dziga Vertov, 1923)

Since Dziga Vertov’s kinoki team or ‘cinema-eye’ launched the journal Kino Pravda (Film Truth) in 1922, and Walter Benjamin compared the cameraman to a surgeon in 1935, the lens ready to ‘pry an object from its shell,’ the eye of the camera has made architecture infinitely available to the masses, establishing itself as the most relevant projective interface to the experience of 3D space.

Camera Eye is an ongoing investigation that focuses on the exploration of film as a design medium in the practice of architecture. It advocates cinema as the key technology for constructing projected realities and a practical fluency in the language of montage as a significant chapter in the education of any designer today.

‘Camera Eye’ research studio

The object of this course is the exploration of film as a representational medium in the design and practice of architecture. The experiment contends that the language of film, with its host of kin technologies (video & digital) capable of rendering time-based processes and perception intelligible – as described by Sigfried Giedeon when speaking of the houses in Pessac by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in 1928: ‘only film can make the new architecture intelligible’– may hold the key to the future of a representational system in crisis, currently unable to cope with the increasingly complex demands to organize and visualize both the physical subtleties and structural logics of contemporary design production.

Choreaography vs. Geography

The use of architecture in all forms of film art, from fiction to documentary and other non-narrative examples, such as Bill Viola’s recent work in The Passions, has traditionally invested the experience of form with meaning. From Fritz

Lang's Metropolis to Antonioni's architectural construction of anxiety in L'Avventura or Ridley Scott's Blade Runner this phenomenon has been widely documented by countless debates in film theory. Film predates architecture under the premise that it requires fixity and framing as orientation devices, however the opposite may result more accurate: more often than not it is architecture that increasingly demands notation for the complexity of time-based variation and change, signaling a fundamental break with the older medium of architectural imagery of the tableau map in its organization of parts and geographical units. It is our task to chart the cinematic map of the deployment of architecture or rather, its choreography.

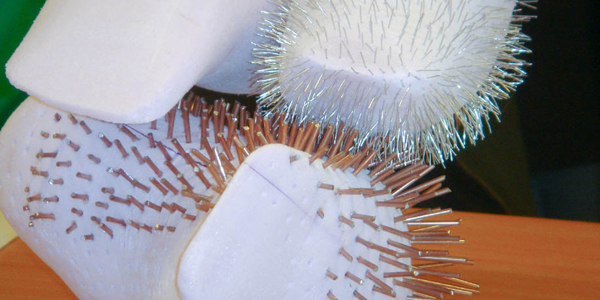

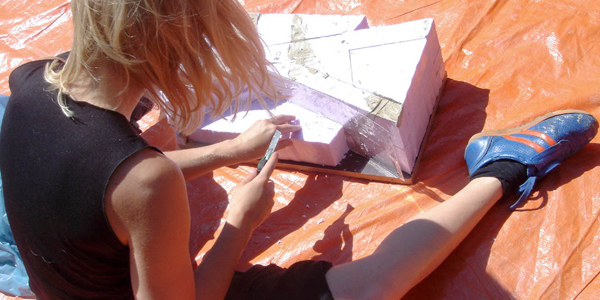

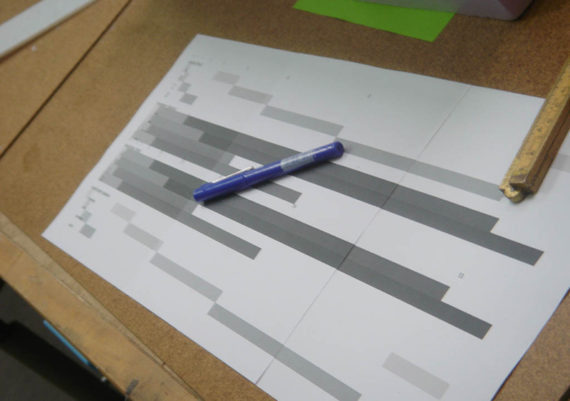

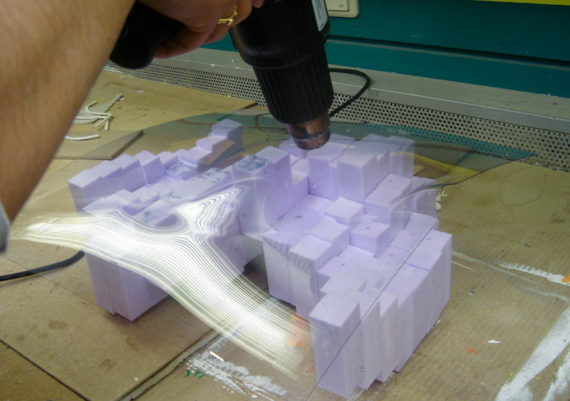

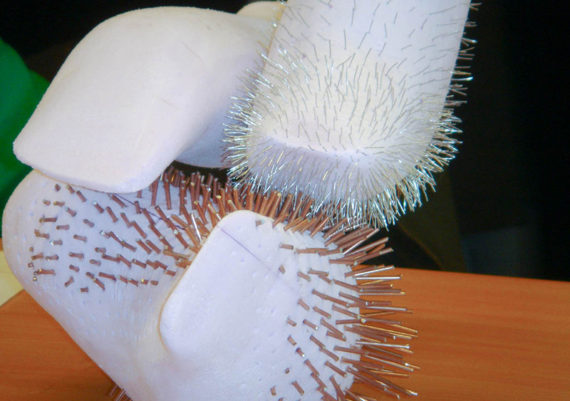

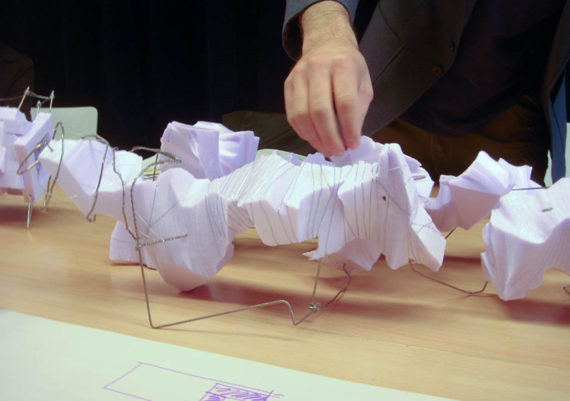

From analysis to design instrumentation: film-space transcription

The research studio is structured in two halves divided by a mirror line. In the first half the students analyze examples from film design by abstracting their time and spatial construction into diagrams and are then asked to produce a short film that illustrates their findings in the form of visual and sound editing patterns. In this phase architecture, as the subject of the film to be produced, is used as a performance medium for the interpretation of abstract notation. In the second half, the students are asked to design possible transcriptions of their films by means of building models with different materials: foam, wire and concrete. In doing so, they are forced to reverse the direction of the first process, translating elements of film language (their own film compositions) onto the medium of architecture in order to provide a structural framework to the design task.

The aim of this exercise is to explore the value of an abstract methodological approach, understood as a design mechanism, where we are at once confronted with the language of a parallel medium (in this case film) that regards time as a design variable, and simultaneously removed from the conventional frame of reference of 'compositional' thinking in architecture.

Olga Vazquez-Ruano

(published in Camera Eye Report)